The Basics blog posts are a series of posts designed for people who want to learn more about unconventional multistage completions systems, but do not have experience in well completions or an oil and gas background. The goal of this series is to explain technical subjects in a simple and easy to understand manner, so that beginners can learn more about the subject matter.

As the title suggests, this post is focused on what hydraulic fracturing is and why it is required in these “unconventional” rock formations. Although hydraulic fracturing is often given all the credit for unlocking these formations, there are two other technologies that are most often needed for economically producing wells – horizontal drilling and multistage completions. This post gives an overview of all of these technologies, why they are needed, and the overall completion process in this application.

In the last several years the United States has become the world’s largest producer of both oil and gas, with the states of Texas and North Dakota individually producing more oil than some countries in the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). This rapid increase in production comes from combining processes used in the oil and gas industry for many years, and applying them to “unconventional” rock formations that were previously uneconomical. These three processes are horizontal drilling, hydraulic fracturing, and multistage isolation. Unfortunately, due to misinformation in the media, there is mass confusion on what hydraulic fracturing actually is. In an attempt to clear up some confusion, this blog post will explain these processes in layman’s terms and show how the combination of these techniques has unlocked the oil and gas in these low-permeability reservoirs. Although I have the itch to jump into the mass amount of misinformation out there, I’ll have to wait address those in later blogs.

Very simply put, the ability of the fluid to flow through the pores in the rock is called permeability. Conventional oil and gas reservoirs have a high enough permeability that if you place and complete a well in the targeted area, the oil and gas will flow though the pores in the rock with little to no stimulation of the rock. In fact, oil and gas will naturally seep to the surface if it is not trapped by a geological zone that has little to no permeability. That’s actually how humans discovered oil and gas, it naturally seeps to the surface!

Unconventional rock formations do not have enough permeability for oil and/or gas to flow into the wellbore at significant flow rates. These types of formations are also referred to as “tight” formations, because the low-permeability rock is so tight that fluid cannot flow through the rock easily. The key to unlocking these types of formations is to get as much contact area as possible and to create artificial permeability. Let’s start by discussing how to increase the contact area.

Horizontal Drilling

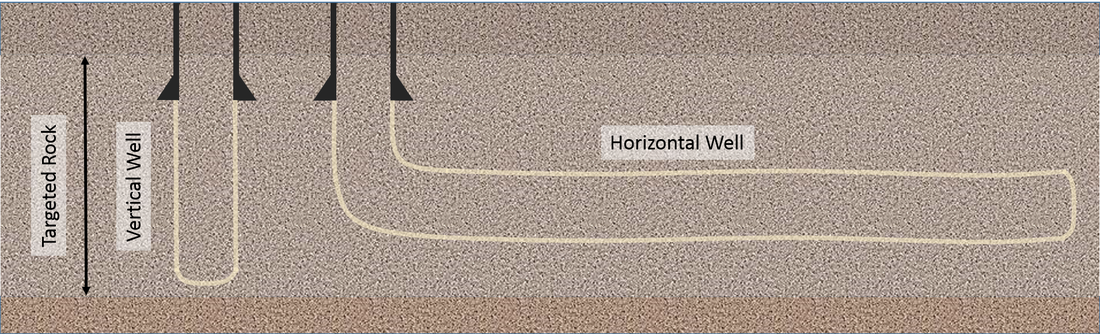

Horizontal drilling is the practice of drilling a well horizontally into the targeted reservoir to gain more contact area. This horizontal portion of the well, or the lateral, follows the direction of the reservoir to add more contact area to the rock, providing access to much larger volumes of oil and/or gas. According to a report from the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) on horizontal drilling (EIA 1993), the first true horizontal well was drilled in Texon, TX in 1929. Improvements in technology made the concept a much more viable option in the 1980’s, and there were over 1,000 horizontal wells drilled by 1990. Fig. 1 shows the increased contact area of a horizontal well compared to a vertical well.

Hydraulic Fracturing

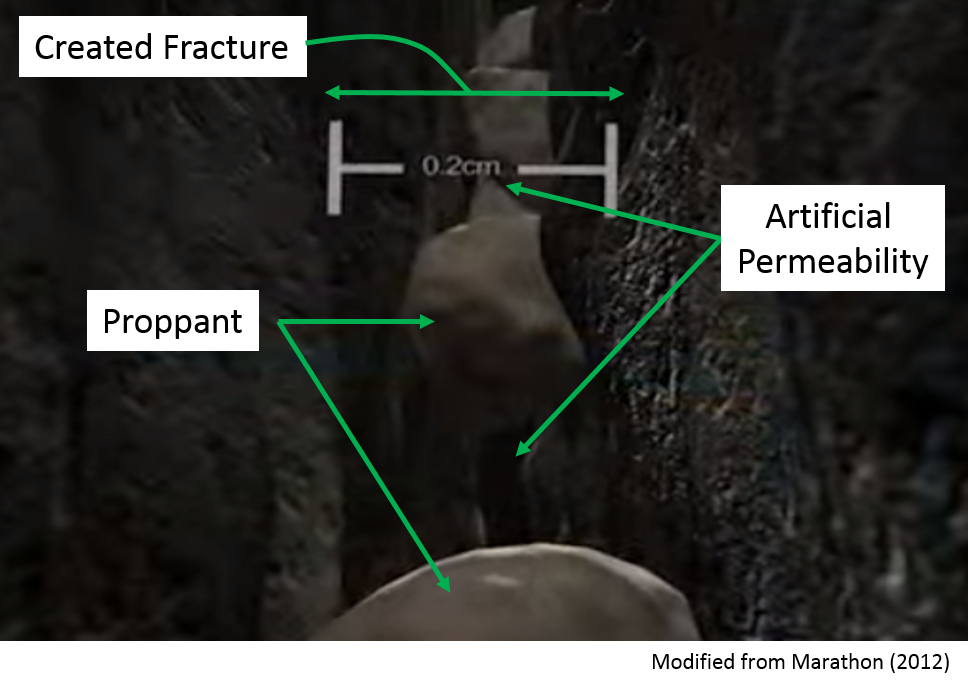

These rock formations have such a low permeability that the oil or gas will not flow to surface just by drilling a hole into the targeted rock formation, at least not at an economical flow rate. The purpose of hydraulic fracturing is to create artificial permeability in the rock so the oil or gas has a pathway to flow into the wellbore. A hydraulic fracturing treatment works by applying enough pressure to crack or fracture the rock. Once the rock near the wellbore is fractured, additional fluid is pumped into the reservoir at high pressures to continue cracking the rock outside of the wellbore to optimize the amount of contact area. While the fluid is being pumped into the well, proppant is mixed into the fluid and pumped into the fracture. This proppant is often sand but can be a manmade material, like a ceramic, and it is used to keep the fracture “propped” open once the pressure is released from the rock. Without the proppant in the created fractures, the rock would reclose and reseal with nearly the same permeability as before it was fractured. The pore space and the flow area around the proppant creates the artificial permeability and the hydrocarbons can flow through the fracture. Fig. 2 shows the proppant propping open the created fractured, creating the artificial permeability.

Multistage Isolation

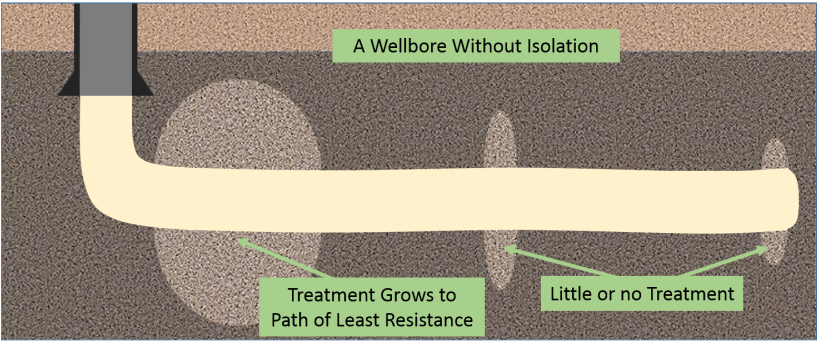

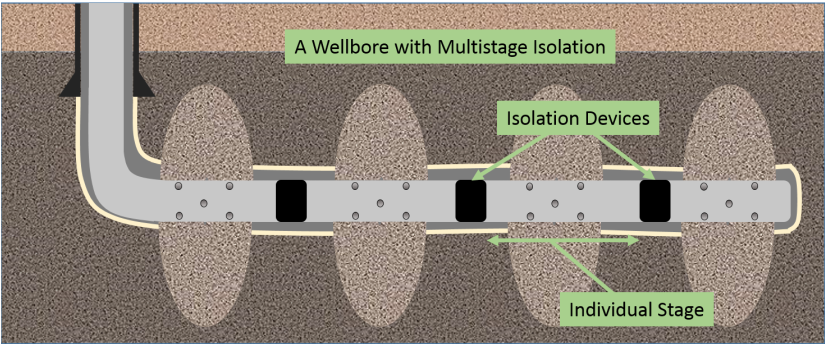

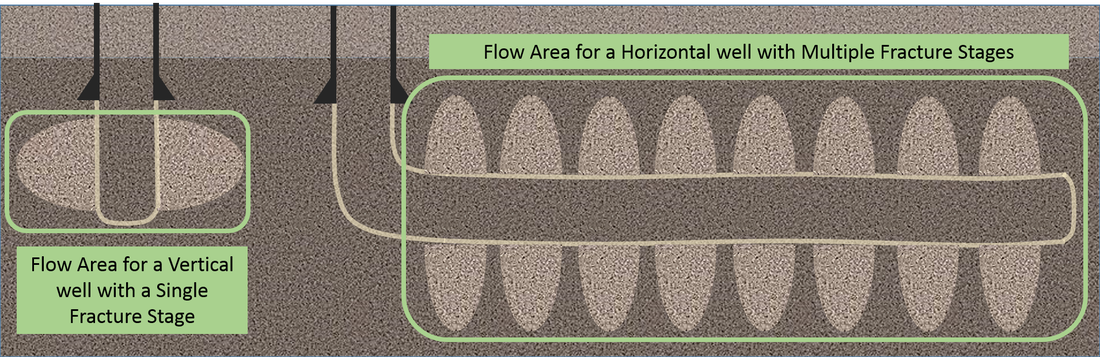

Multistage isolation is the practice of breaking the horizontal lateral into several pieces called stages, and hydraulically fracturing the stages individually. This technique was the last piece of the puzzle to unlock the oil and gas from low-permeability reservoirs, because the stages maximized the effective flow area for the oil and gas. A single fracture treatment in the wellbore will fracture the weaker rock and not distribute across the entire lateral as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The combination of these techniques gives us the ability to produce these low-permeability reservoirs at economical rates. This is achieved by drilling a horizontal wellbore that has a much larger contact area than traditional vertical wells, creating artificial permeability with hydraulic fracturing, and dividing the wellbore into multiple stages to increase the flow area throughout the entire lateral. Fig. 5 shows the final result of combining these three techniques compared to a vertical well with a single stage.

References

- EIA. 1993. Drilling Sideways – A Review of Horizontal Well Technology and Its Domestic Application. Report No. DOE/EIA-TR-0565, US EIA, US DOE, Washington, DC (April 1993)

- Halliburton. 2015. Hydraulic Fracturing 101, http://www.halliburton.com/public/projects/pubsdata/hydraulic_fracturing/fracturing_101.html (accessed 21 September 2015)

- Frac Focus. 2015. A Historic Perspective, https://fracfocus.org/hydraulic-fracturing-how-it-works/history-hydraulic-fracturing (accessed 21 September 2015)

- Marathon Oil Corporation. 2012. Animation of Hydraulic Fracturing (fracking). https://youtu.be/VY34PQUiwOQ (accessed 21 September 2015)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed